Oleksandr Barvinsky ID: 271

Oleksandr Barvinsky ID: 271

1847-1926

A Ukrainian conservative politician, educator and historian.

A member of the House of Deputies (1891–1907) and the House of Lords (1917–1918) of the Imperial Council in Vienna, a member of the Galician Provincial Diet (1894–1904), Minister of Education and Religions in the government of the ZUNR (1918–1919), chairman of the Shevchenko Scientific Society (1892–1897), head of the Ruthenian Pedagogical Society (1891–1896), member of the Provincial School Council (1893–1918), a government adviser (from 1906), a court adviser (from 1910).

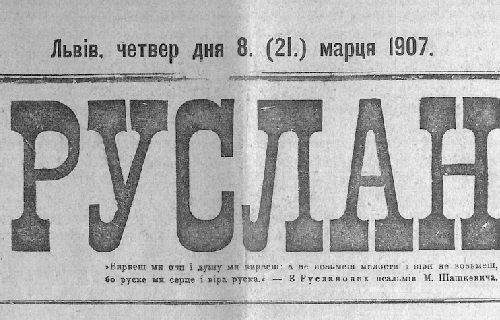

Oleksandr Barvinsky was born on June 8, 1847 in the village of Shliakhtyntsi (now Zbarazh rayon, Ternopil oblast) and died on December 25, 1926 in Lviv. Together with his wife Yevhenia, he is buried in the Barvinsky family tomb at the Lychakivsky cemetery. His father was a Greek-Catholic priest, the family being, however, of noble origin (the Barvinskys’ family coat of arms is the Jastrzębiec). He got his secondary education at the German gymnasium in Ternopil. In 1868, he successfully completed his studies at the Faculty of Philosophy of Lviv University. During his studies, special emphasis was placed on the study of history, literature, and Slavic languages. The years of 1868–1888 are the "Ternopil" period of Oleksandr Barvinsky's life. He worked as a teacher at the teachers’ gymnasiums in Berezhany (1868–1871) and Ternopil (from 1871). During this time, he took an active part in the activities and development of the populist movement in the Ternopil region, founding branches of the Prosvita society and giving popular science lectures on the history of Ukraine. Together with his brother Volodymyr, he was at the origins of the first daily newspaper of the Galician populists, the Dilo. In 1888, he and his family moved to Lviv, where they lived at ul. Sobieshchyzna 5 (now vul. Barvinskykh).

From that moment on, Barvinsky actively participated in "big politics", becoming one of the key figures of the socio-political life in Galicia; he was a co-creator of the "new era" policy (attempt at a Polish-Ukrainian mutual understanding, 1890–1894) and was repeatedly elected a member of the State Council and the Galician Diet. After the failure of the "new era", he continued to defend the idea of interethnic understanding and became the founder and, until the early 1920s, the unchanged leader of the conservative Christian social movement. After the final transfer of Eastern Galicia to Poland in 1923, he withdrew from active political life, focusing on scientific work and writing memoirs.

Among the contemporary Ukrainian Galician politicians, Oleksandr Barvinsky stood out in two aspects. The first was his loyalty to the idea of "organic labour." It consisted in abandoning high-flown, pathetic, and unfeasible slogans like those about the division of Galicia and making maximum efforts for the comprehensive development of Ukrainian society, raising the level of its political culture, improving the socio-economic situation (especially that of the peasantry) and education. Only in this way, according to Barvinsky, the Ukrainians could become a significant political factor in the Habsburg monarchy and, in an undefined perspective, prepare for the creation of their own state.

The second aspect, directly related to the previous one, was "real" politics. Barvinsky understood the importance of compromises in politics more than any other of contemporary Ukrainian politicians in Galicia. Having started his own active political career with a key role in the "new era", he later considered it a good example and a valuable experience. Unlike the leaders of the chief Galician Ukrainian political parties (Yulian Romanchuk, Yevhen Olesnytsky and others) and the general majority of Ukrainian society in the province, Barvinsky did not consider constant opposition and sporadic hostility toward the Polish elites in Galicia or the government in Vienna to be a politically promising strategy. According to this conservative politician, given the weakness of Ukrainian society (until the implementation of the "organic labour" idea), it was worth seeking the smallest possible concessions, compromises, and local agreements. For example, not to demand the opening of a Ukrainian university "here and now", but to engage in the general development of education, to seek an understanding with the majority of the Galician Diet and Austrian ministers regarding the opening of new Ukrainian schools and gymnasiums, to prepare the scholarly personnel necessary for a Ukrainian university, etc. So it is not surprising that Barvinsky was a supporter neither of student actions like the so-called 1901 secession, nor of "street politics" in general.

Skeptical attitude towards the political activity of students was one of the main features of Barvinsky as an educator. Both as a gymnasium teacher and as a member of the National School Council, he always insisted that the main task of youth was to acquire knowledge and qualifications that would help them to take over the reins of society from the older generation in the future. Until young people were ready for this function, they should not be distracted by extracurricular, "street" activities. In view of this, Barvinsky also did not approve of an idea that was widespread in Ukrainian society and called gymnasium and university students to occupy advanced positions in the political struggle: "Everyone here seemed to be born a politician, and any gymnasium graduate or university student considered himself called to solve far-reaching and difficult political, national and social issues..."

The ideas about the ways of development of Galician Ukrainians that were different from those of the majority of politicians and the whole society and insisting on the need to find compromises at a time when modern (and far from always moderate) nationalism was spreading and strengthening in Galicia, among both the Ukrainians and Poles, led to the formation of a false image Barvinsky as a "masters’ servant", a "salon Ruthenian" or a "compromiser." Although undeserved, these labels accompanied his political activity invariably and significantly contributed to the failure of the Christian social movement created by Barvinsky.

Moreover, his opponents transferred their rejection and hostility towards Barvinsky's political concepts to the politician's family. It was for these reasons that Mykhailo Hrushevsky refused to be the scientific supervisor for a history project by Oleksandr Barvinsky's son, Bohdan. Oleksandr Barvinsky was also forced to transfer his another son, Vasyl (a future famous composer), from the Ukrainian gymnasium to the Polish one due to bullying, primarily by some of the teachers. In the eyes of his enemies, doing this only strengthened his negative image.

Related buildings and spaces

People

Organizations

Sources

- Олександр Барвінський, Осип Маковей, Кирило Студинський, В оборонї правди і чести, (Львів, 1911).

- Олена Аркуша, Олександр Барвінський (до 150-річчя від дня народження), (Львів: Інститут українознавства НАН України, 1997).

- Ігор Чорновол, "Тягар прагматизму, або Олександр Барвінський у світлі сучасності", Барвінський О. Спомини з мого життя. Т. 1, (Київ: Смолоскип, 2004), 17–35.

- Наші християнські суспільники, (Львів, 1910).