Vul. Ivana Franka, 39 – residential building ID: 1090

The three-storied house on the corner of Franka and Kostomarova streets was built on the banks of the Poltva River in 1892-1893. Commissioned by the developer Szymon Frey, it was designed by architect Andrzej Gołąb. It is a typical Historicist-style rental townhouse.

Story

For most of the nineteenth century, this section of today's Franka street (beyond the intersection with Zelena street) and further from the city center was called ul. Stryjska. Already at the turn of the nineteenth century, a triangular plot was formed here. It lay next to where the street intersected with the Poltva River, which flowed along the present-day Kostomarova and Saksahanskoho streets. Almost until the twentieth century, the houses here as well as in the entire neighborhood, retained a completely suburban character. They were mostly single-storied, had narrow street façades, and extended deep into the plots. Built of brick, they had steep shingle roofs. This was the case with the house at ul. Stryjska 9 (now vul. Franka 39), which had a conscription number 349 ¼ and stood there until 1892.

Project documentation for this old building did not survive; however, historical maps of Lviv evidence that it was built in the 1820s. In 1853, Józef and Rozalia Słoński owned it. These people may have been related to Baron Ignacy Słoński (Ostoja coat-of arms), a clerk of the Galician Governor's Office, whose name and position indicate the status of an impoverished nobleman. Between 1856 and 1863, the house was owned by Józefa Słońska and Peter Tarler, a forensic expert for consumer products at the Lviv Magistrate. Between 1863 and 1871 the plot was divided into two parts. The smaller one, located on the corner next to the river, received a new address: 926 ¼ or ul. Stryjska 7, while the larger one retained the old number 349 ¼ or ul. Stryjska 9. Most likely, the plot was divided in 1866. In the early twentieth century, the two parts were reunited.

Housing for poor Lvivians on the bank of the Poltva River

In 1866, the owner of the single-storied house was Józef Goliński. Hiring a builder named Stanikowski, he began adding two rooms with a kitchen, a shop, and a basement to his house. Having submitted the architectural project to the Lviv magistrate, he did not wait for the official approval to be granted. On July 2 of that year, a magistrate's commission arrived on Stryjska street and confirmed that the owner had begun constructing foundations and brick walls. In addition to being unauthorized, these walls were so thin that they violated the current Lviv Building Statute of 1855. Józef Goliński was fined and demanded to commission a project from a professional builder. The city authorities had no objections to the new drawings made by Jakob Zwilling (DALO 2/3/887:1-4, 69). The construction was completed in a few weeks. On August 25, Goliński received an official permit for the building, prepared by Alfred Bojarski on behalf of the then chief architect of Lviv, Władysław Zapałowicz (DALO 2/3/887:6).

This small outhouse probably became the home and shop for Józef and Rosalia Goliński, who separated it into a separate plot at ul. Stryjska 9 (conscription number 726 ¼). They sold their old house; in 1871, it was owned by Jan Kruk (Skorowidz, 1871), in 1873, by Jędrzej Węgłowski and Michał Dyla; in 1879, by Michał and Karolina Dyla (Skorowidz, 1879). In 1873, Węgłowski and Dyla received a request from the Magistrate to immediately repair damaged gutters and sewage pipes in the house, which indicates its dilapidated condition (DALO 2/3/887:8).

In 1879, the property at ul. Stryjska 9 was purchased by Yossel (or Joseph) Zuckerberg. He lived then on ul. Bożnicza (today, vul. Sianska), the center of the traditional suburban Jewish neighborhood. The apartments on Stryjska street were leased out. In December 1879, he asked the Magistrate to allow him to replace a window with a door, which was readily granted with the proviso that he not make any protruding elements on the sidewalk; so, another shop had to be located there (DALO 2/3/887:9-10).

Zuckerberg apparently had a conflict with one or more of the tenants, because a year after buying the house, Daniel Stadnik complained about him, identifying himself in a letter to the Magistrate as a former resident of the house. He wrote that the plot owned by "Berko Zucker, also known as Zuckerberg" was not kept clean, with dirt and garbage accumulating there. The wooden fence, he said, was pushed all the way to the edge of the Poltva, had a hole in it near the stables, and garbage was also falling down to the river. A Magistrate commission, headed by Alfred Bojarski, did not see the described condition on the spot, and the complaint was filed in the archives as being without substance (DALO 2/3/887:11-12).

Five years later, in the summer of 1886, however, the same official and architect Bojarski saw Zuckerberg begin unauthorized roof repairs on his house. The old shingle roof was leaky and was being patched. The city authorities encouraged the property owners in every way possible and demanded that they replace the shingles with fire-proof tin rather than repair the holes. However, when Bojarski came to check and stop the unauthorized repairs, he found that the ceiling had sagged, the rooms were less than 2.5 meters high, the rafters were moldy, and the walls were damp and fragile. He wrote a report stating that the house "qualified for eviction and demolition" and that the owner should build a new three-storied townhouse, like those that had recently been built on the outskirts of what was then Stryjska street. Zuckerberg was fined 5 rhenish guldens and demanded to evict the people and reconstruct the building by the end of October (DALO 2/3/887:13).

This began a several-year-long legal battle between the city authorities and Joseph Zuckerberg. His letters contain various excuses, ranging from the fact that he was vacationing at the baths of Velykyi Lubin (pl. Wielki Lubień) near Lviv at the time and did not know about the repair, to the fact that he was a poor father of a large family who did not have the finances to fulfill the city authorities's requirements. He argued that an independent commission with builders (Josef) Engel and (Wincenty) Kuźniewicz had recognized that the house remained eligible for repair. He explained that the low ceilings were a product of different time, when such height was not prohibited. Zuckerberg also claimed that it was unprofitable to reconstruct the house completely as it catered to the needs of the poorest clientele. He laid out these arguments in a letter dated 7 August 1886, sent from ul. Szpitalna, 7 (DALO 2/3/887:18). The City Council, which considered his appeal in September, decided to make concessions.

Alfred Bojarski further insisted that, if not the entire house, its old and destroyed wooden toilet on the riverbank should be demolished and replaced with a new one. At that time, the toilet had a cesspool dug in the ground and connected to no sewage system. The architect noted that it was extremely unhygienic and polluted the Poltva, which violated Lviv's Building Statute of 1885; and the best solution according to him was to build a new toilet with a masonry sewage collector. Another commission confirmed during an inspection that the toilet was indeed in an unacceptable condition; however, all the toilets in the neighbourhood were no better (DALO 2/3/887:21-25).

In January 1887, Zuckerberg told the Magistrate that he felt hurt by the decision of the city authorities. According to him, he was in debt and had decided to sell the property, so the toilet should be a problem for the future owners. His letter of appeal was considered at a meeting of the City Council, and eventually the 3rd Department of the Magistrate granted a postponement, and then several more, hoping Zuckerberg would finally build a new toilet. The case was reviewed by the Governor's Office as the higher instance, and the further appeals were rejected. The owner was repeatedly notified of the fine imposed on him.

Eventually, Stanisław Goliński, probably a relative of Józef's, the owner of the aforementioned outhouse from 1866 (under a separate address, 726 ¼), appealed to the Magistrate. He also asked for a postponement of the request, citing a lack of funds and the fact that there were only two tenants in the house. In 1889, the project for the new toilets, signed by Jakub Danyłewicz as the author, was finally approved (DALO 2/3/887:56-59). The commission that came to inspect the construction demanded this time that the owner demolish the entrance to the attic from the kitchen and repair the bridge over the street ditch. Stanisław Goliński was threatened with a large fine and the sequestration (seizure) of his real estate. In 1890, all the requirements were fulfilled, as Josef Zuckerberg informed the Magistrate. But he also wanted to put a boiler surrounded by wooden walls (?) on the plot, which the Magistrate explicitly forbade (DALO 2/3/887:60-63).

This is the end of the correspondence preserved in the house's archival file. It is likely that due to Zuckerberg's debt, the property was eventually seized and put up for sale, and thus purchased by Lviv businessman Szymon Frey. At first, this did not apply to the outhouse owned by the Golińskis.

Sewers; covering the river; and modern development of the neighborhood

As early as in the 1870s, the Lviv city council discussed plans to lay a sewer along ul. Stryiska (today, Franka street). There is a mention in 1875 that the street was narrow and inconvenient and had no paved sidewalks from the "military laundry" (today, vul. Franka, 63) (Gazeta Lwowska, 1875, No. 172, p. 4). City council also discussed widening the bridge over Poltva, located right next to ul. Stryjska 9 (Gazeta Lwowska, 1875, No. 211, p. 3). In 1877, the council rejected a number of appeals from local property owners who did not want to invest in the construction of the sewer (Gazeta Lwowska, 1877, No. 4, p. 4). The case was being delayed.

In 1887, this section of ul. Stryjska was renamed ul. Mikołaja Zyblikiewicza in honor of the recently deceased Marshal of the Galician Diet.

In 1888, a plan was designed to cover Poltva, in particular along the present-day vul. Shoty Rustaveli (then ul. Jabłonowskiego), and the city authorities hoped that this would help drain the waterlogged area and facilitate the emergence of new modern housing on the surrounding streets (Gazeta Narodowa, 1888, No. 180, p. 2). The impetus for the construction of sewers in this neighbourhood was the construction of the physics and chemistry faculties' buildings of the Franciscan University on the present-day vul. Kyryla i Mefodiya. In 1891, the construction of the sewerage system continued, and the city council approved an additional loan (Gazeta Narodowa, 1891, No. 135, p. 2).

Poltva in this neighborhood was finally covered around 1912, when the modern Saksahanskoho street (then ul. Tadeusza Romanowicza) and Kostomarova street (then ul. Kącik) appeared.

As the local historian Adam Krajewski summarized this development of the city, “Lviv has been civilized; it has pushed out of the city what was not European, and the good humor of those inhabitants of Lviv who are poorer has given way to general misery and fear of germs with which hygienists poison every minute of the day for people who want to have fun in the open air” (Krajewski, 1910, 56). He devoted his short book to the suburbs of Lviv, which disappeared from the face of the earth in the second half of the nineteenth century due to the emergence of modern urban development.

A three-storied townhouse with a music school and a hairdresser's shop

The townhouse built on this site in 1892-1893 by Szymon Frey originally looked different than today. Although the building appears to have been built in one piece and designed as it is today, it is essentially composed of three parts constructed in different periods.

Frey first acquired the plot 349 ¼ (ul. Zyblikiewicza 9), while the outhouse 926 ¼ (ul. Zyblikiewicza 7) remained owned by the Goliński family. His house therefore had a complex polygonal layout, with the main façade having four windows, not five as it is now (DALO 2/3/887:75). The townhouse was a typical one, simply and unpretentiously decorated with order elements in the Historicist style. On the ground floor there were two shops, one of which was connected to the apartment, with the caretaker's room at the back. On the upper floors there were two apartments with enfilade rooms; toilets could be accessed through a balcony. Rooms were heated by tiled stoves and there was no question of installing baths inside the house at that time.

By 1900, Frey had added two more rooms on the Poltva side, this time along Kostomarova street, commissioning a project from Andrzej Gołąb again. This added three more one-room apartments with kitchens, one on each floor, with entrances from balconies. After that, he sold the building. The new owner, Władysław Hoszowski, a lawyer, soon bought the small outhouse owned by the Golińskis and added the current corner part in 1904, expanding the apartments to the left of the entrance. This extension was designed by an architect Napoleon Łuszczkiewicz. He added a balcony to the main façade, which was not originally present there, and decorated the corner part with Neo-Baroque balconies topping it with an attic (DALO 2/3/887:70-72).

New townhouse's residents were middle-class, unlike those who lived in the previous building, whom the owner Josef Zuckerberg described in the late 1880s as "the poorest".

In 1900-1939, a hairdresser's shop was located on the first floor to the left of the entrance. On the right, Stanisław Greń's basket shop operated for many years. In one of the second floor apartments, a violin school run by Robert Poselt operated from 1899.

Elegant cars and a petrol station in the neighborhood

For many decades, the townhouse at ul. Zyblikiewicza, 9 was adjacent to the elongated house of the locksmith Ludwik Jasieński; the appearance of this townhouse is captured in an archival photo. The townhouse further on, at number 13, still had a firewood warehouse in it in 1929 (Chwila, 1929, No. 3833, p. 14). These houses reminded of this neighborhood's old suburban character well into interwar period, demolished in the early 1930s.

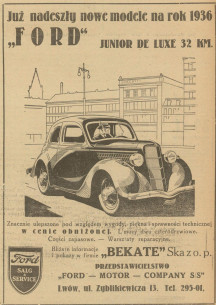

In April 1933, the BEKATE company was registered in Lviv, the name being an abbreviation of the names of three partners: Jan Bielski, Dr. Stanisław Tabisz, and Edward Kreps. The limited liability company was engaged in car service and received the status of the American company Ford Motors Company cars official distributor. The company presented cars at the annual "Targi Wschodnie" exhibitions in the Stryiskyi Park — this was described in contemporary press (e.g. Czas, 1935, No. 60, p. 12).

The BEKATE company settled in the neighborhood demolishing old houses, building a fashionable car dealership along the street and setting up repair shops in the depths of the plot; it also invited the Karpaty company to build a petrol station. Their business was launched in July 1933 and operated at least until the outbreak of the Second World War. At least seven petrol stations of this kind were located in Lviv at that time; there were more than 30 car repair shops in the city in 1938 (Polski skorowidz samochodowy, 1938, 182).

Today, these buildings, which have not survived, are only reminded of by a colored inscription on the firewall of the building at vul. Franka 43, as later plaster and paint is peeling off. The location of a car service explains why the area behind the building at vul. Franka, 39 was never built up.

Architecture

The previous house at the present-day address of vul. Franka 39, probably built in the 1820s, was a single-storied L-shaped building. Its main façade was 11.38 m long and most likely had five axes, with a passageway in the center and two windows on each side. The passage provided access to a wooden stable and a cart shed that stood on the edge of the plot near the Poltva. It was built of brick and had a shingle roof. One of the houses at the present-day address of vul. Franka 43, which does not exist today, had a similar appearance, except that its main façade had seven axes. The façade had no decorations, the windows had no trimming.

The present-day house, built in 1892-1904, is a typical example of a rental apartment house. According to the 1892 project, the first floor was designed to accomodate two shops: a smaller one to the right of the main entrance, and a larger one to the left, the latter having two residential rooms and a kitchen. The main entrance led to a long hallway and then to a staircase. There, on the right, was located the entrance to the caretaker's apartment; in front there was an exit to the courtyard (from where toilets could be accessed). On the upper floors, there were two double room apartments with kitchens, with access to the toilets via staircase and balcony. No back staircases existed in this house, such as those for servants in wealthier buildings.

The rooms had tiled heating stoves; the kitchens had stoves for cooking. Originally there was no running water, sewage, or electricity. The three-storied brick building had vaulted basements, wooden beam floors, wooden rafter and post roof structure, and a tin roof.

Following the 1900 and 1904 additions, the apartment on the left was enlarged into a five-room one, while the apartment on the right was converted into a one-room one with a kitchen. The wing had a one-room apartment (with a kitchen) that could be accessed through the courtyard (on the ground floor) or through the balcony (on the upper floors).

Façades feature Historicist style, combining Neoclassical and Neo-Baroque motifs, as well as some Secession influence, typical in the early years 1990s. Façades are asymmetrical due to the fact that the building was constructed in three stages and has a pronounced tectonic layout. At the level of the first two floors, the façades are rusticated, with more massive square rustication at the bottom and French rustication at the top; the floors are visually separated by cornices. All window and door openings are rectangular, with no trimmings on the ground floor. On the first and second floors, the openings have profiled trimmings with "ears", topped with triangular pediments on cantilevers (first floor) and keystones (second floor). The façades are crowned with an entablature with a row of dormer windows and a cornice on cantilevers. The corner part of the building is emphasized by a slight projection and two balconies; it was topped with an attic, which has not been preserved.

The shape of the plot was determined by its proximity to the Poltva River, and as of 1904 it was built up to the maximum extent permitted by the regulations. The fenced plot on the side of vul. Kostomarova did not actually belong to the house at the present address of vul. Franka 39, but to the adjacent one, which is now part of vul. Franka 41.

People

Jan Bielski— partner at the BEKATE firm, the official distributor for the Ford-Motors-Company in the Polish Republic. The firm owned an car

salon, repair workshop, as well as a gas station on the neighboring plot

(Franka 41).

Alfred Bojarski— architect who worked at the municipal Building Department.

Jakób Danilewicz — a workman who drew up plans for a toilet building.

Jędrzej Węgłowski — co-owner of the previous house on this plot in the 1870s.

Michał and Karolina Dyla — co-owners

of the previous house on this plot in the 1870s.

Joseph Engel — architect and contractor in Lviv.

Szymon Frey — a developer who originally commissioned this building.

Józef Goliński— co-owner of the

previous house on this plot; from 1866, he owned a two-room annex (then ul. Stryjska, 7).

Stanisław Goliński— co-owner of the two-room

annex in the 1860s – 1870s(then ul.

Stryjska, 7).

Andrzej Gołąb — architect and contractor; he designed the building in 1892 and its

outhouse in 1900.

Stanisław Greń — owner of a basket shop, which was located for decades in this building

before 1939.

Władysław Hoszowski — lawyer who owned the

building around 1901–1939.

Ludwik Jasieński — locksmith who owned the neigboring building 11 (today Franka 41).

Edward Kreps — partner at the BEKATE firm, the official distributor for the Ford-Motors-Company in the Polish Republic. The firm owned an car

salon, repair workshop, as well as a gas station on the neighboring plot

(Franka 41).

Jan Kruk — co-owner of the previous house in 1871.

Wincenty Kuźniewicz— architect and contractor.

Napoleon Łuszczkiewicz — architect who designed an annex to the building and changed the façade

décor.

Robert Poselt — musician, head of a violin musical school which was located in this

building from 1898.

Józef, Rozalia Słoński— co-owners of

the previous house around 1856.

Peter Tarler— forensic expert for consumer products at the Lviv Magistrate, co-owner

of the previous house around 1863.

Daniel Stadnik — tenant of the former house in the early 1880s.

Stanikowski — workman who oversaw

the construction of an annex to the former house in 1866.

Stanisław Tabisz — partner at the BEKATE firm, the official distributor for the Ford-Motors-Company in the Polish Republic. The firm owned an car

salon, repair workshop, as well as a gas station on the neighboring plot

(Franka 41).

Władysław Zapałowicz— head of the municipal Building Department in 1869–1872.

Józef Zuckerberg also called Jossel Zuckerberg or Berek Zucker — owner of the previous

house in 1879–1889.

Sources

1. State Archive of Lviv

Oblast (DALO) 2/3/887.

2. Adam Krajewski, Biblioteka Lwowska, T. VIII. Przedmieścia

Lwowskie: obrazki i szkice z przed pół wieku, (Lwów: Towarzystwo miłośników

przeszłości Lwowa, 1910), 70.

3. Chwila, 1929, Nr. 3833, s. 14.

4. Czas, 1935, Nr. 60, s. 12.

5. Księga adresowa królewskiego

stołecznego miasta Lwowa (Lwów, 1897).

6. Księga adresowa królewskiego

stołecznego miasta Lwowa (Lwów, 1900).

7. Księga adresowa królewskiego

stołecznego miasta Lwowa (Lwów, 1901).

8. Księga adresowa królewskiego

stołecznego miasta Lwowa (Lwów, 1904).

9. Księga adresowa królewskiego

stołecznego miasta Lwowa (Lwów, 1913).

10. Księga adresowa Małopołski,

(Lwów. Stanisławów. Tarnopól, 1935–1936).

11. Polski skorowidz samochodowy, 1938, 182.

12. Skorowidz królewskiego

stołecznego miasta Lwowa (Lemberg, 1872).

13. Skorowidz królewskiego

stołecznego miasta Lwowa (Lemberg, 1889).

14. Skorowidz królewskiego

stołecznego miasta Lwowa (Lwów, 1910).

15. Skorowidz królewskiego stołecznego

miasta Lwowa (Lwów, 1916).

16. Neu verbesserte Wegweiser

der Kön. Haupstadt Lemberg (Lemberg, 1863).

17. Wegweiser der Kön.

Haupstadt Lemberg (Lemberg, 1856).

18. "Kronika/Z Rady

miejskiej", Gazeta Lwowska,

1875, Nr. 172, s. 4.

19. "Kronika/Z Rady miejskiej", Gazeta Lwowska, 1875, Nr. 211, s. 3.

20. "Kronika/Z Rady miejskiej", Gazeta Lwowska, 1877, Nr. 4, s. 4.

21. "Kronika/Z Rady miejskiej", Gazeta Narodowa, 1888, Nr. 180, s. 2.

22. "Kronika/Z Rady miejskiej", Gazeta Narodowa, 1891, Nr. 135, s. 2.

Citation

Olha Zarechnyuk. "Vul. Ivana Franka, 39 – residential building". Lviv Interactive. Transl. by Andriy Masliukh (Center for Urban History 2024). URL: https://lia.lvivcenter.org/uk/objects/franka-39/