The Prospect Svobody Promenade (formerly the Hetman Ramparts) ID: 2004

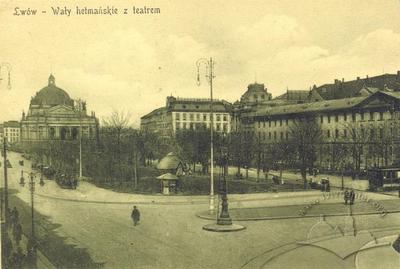

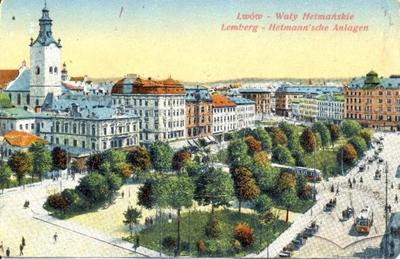

The Prospect Svobody Promenade – formerly, the Hetman Ramparts – was laid in on top of the western section of the historic defensive fortifications that ringed Lviv. The walls were pulled down sometime around 1776 and put into public service of the city. In the first half of the 19th century, parallel streets were established on the eastern and western banks of the Poltva River, and landscaped in rows of poplar; the streets would one day become the boulevard that is Prospect Svobody. In the late 1880s, arched bridges spanned the gap between Maryatska Square (currently, Mickiewicz Square) and Golukhovska Square (currently, Torhova Square). Between 1888-1890, under the direction of Arnold Röhring, the area enclosing the underground river channel was planted in trees and flowerbeds.

Story

Between the river and the city walls at the so-called Jesuit Gate, a defensive embankment and moat had stood since antiquity on the site of the Hetman’s Ramparts. When the walls came down, the ruins were used to fill in the resulting depression and level the ground in order to convert it into a pedestrian thoroughfare. The landfill collapsed in several locations (the area was being utilized by city residents as grazing land for cattle), causing damage to the new promenade. “There were the ramparts (a path) on the western side, lined with willows standing over the Poltva. It was the only place for an evening stroll, but with no real way down, except through a swampy gulch, a slow-paced walk lasting about ten minutes”. (Stankiewicz, 1928, 64).

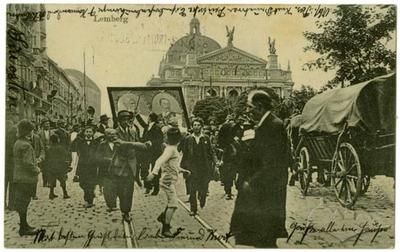

Despite these problems, the “ramparts” soon became a popular spot for a stroll, and by the close of the 19th century, a second ‘city center’ – after Rynok Square – had begun to take shape in Lviv. Medieval Lviv and its Market Square (Rynok Square), which had been laid out to conform to the stipulations of the Magdeburg Charter, now shifted its center to the west, near the new promenade and the surrounding park.

The current layout of the Hetman Ramparts reflects the Biedermeier (19th c., German design) motif. Parallel streets were established along the western and eastern banks of the Poltva, and connected by bridges; the water level in the river was controlled by two locks. Impressive structures went up on either side of the stream, the Hausner building and the Skarbek Theater. Rows of poplar were planted along the new roads (the foundation of the current boulevard). This is the view of the “eastern ramparts” often captured in watercolors from the period, painted to commemorate the 1853 Archduke Karl Ludwig’s visit to the city. The popularity of the promenade continued to grow during the mid-19th century, and splendid kiosks offering lemonade, confectionery, and ice cream could be found along the walk.

The look of the Hetman Ramparts changed with the reforms and economic transition of the 1860s, resulting in new and unexpected features finding their way to the space. Besides the ‘respectable’ public which frequented the area, a black market, and opportunistic – largely Jewish – financial sector saw the ramparts as a desirable location in which to pursue their business. According to eyewitnesses, during the Viennese Financial Crash of 1873, the promenade often resembled a scene straight out of Dante’s “Inferno”.

The new era of the Hetman Ramparts is marked by the enclosure of the Poltva and its conversion into a covered, underground canal. Once a clear-running river, by the second half of the 19th century the Poltva had become an open city sewer. Between 1887 and 1889, sections of the river running between Maryanska and Golukhovska (presently, Mickiewicz and Torhova) Squares were covered with stone arches. The Hetman Ramparts were ultimately converted into a pedestrian boulevard, a configuration which it maintains to the present day (Miasto Lwów, 1896, 322-323).

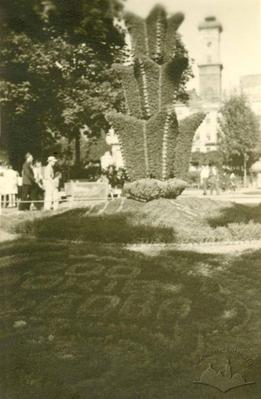

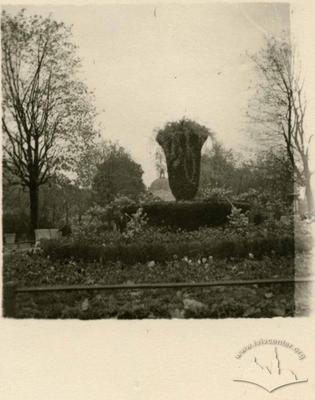

Trees and flower beds were planted here between 1888 and 1890 under the direction of Lviv municipal gardens supervisor Arnold Röhring (Miasto Lwów, 1896, 318-320). The area’s architectural ensemble underwent significant change during the period, with the construction of the immense Galician Savings Bank, the Museum of Industry, and the Municipal Theater.

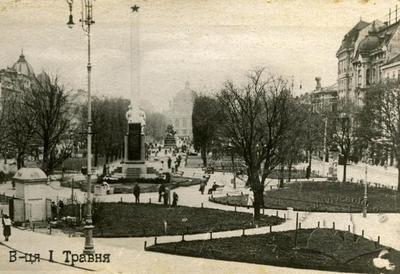

In 1859, the first monument – a stone statue of Hetman Stanislaw Jabłonowski – was erected on the ramparts. Strictly speaking, it is from this period that the western ramparts, promenade, and park first began to be referred to as the “Hetman” ramparts

Architecture

The Prospect Svobody Promenade – formerly the Hetman Ramparts – runs on a north-south line through the center of Lviv. At its northern end stands the Opera Theater, and at its southern, the Adam Mickiewicz Memorial. The architectural ensemble surrounding the greenway combines elements of late classicism (as in the former Skarbek Theater), and historicism (the former Galician Savings Bank, and Museum of Industry).

The promenade is situated above the channel of the Poltva River which has been converted into a culvert. Flowing under Prospect Svobody, the river serves as the topographical east-west dividing line of the city. Zamkova Hora (Castle Hill) marks the eastern edge of the river valley, with Piskova Hora behind it, and finally, Znesinnya Ridge. On the western edge are Kortumova Hora, St. George Hill, and the Citadel. These heights and their surrounding foothills form a natural amphitheater around the Lviv lowlands.

The promenade is located on the site where the former city walls and ramparts met. Near the end of the 18th century the fortifications were brought down, and the area was landscaped and converted into a pedestrian park.

The arrangement of the Hetman Ramparts was arrived at in the 19th century with the laying in of parallel streets – formerly known as Karl Ludwig and Hetman Streets – now combined into one, Prospect Svobody. Prior to the enclosure of the Poltva, the area was laid out as a boulevard with a park promenade through its center, and trees planted and flowers arranged in beds in a style reminiscent of the Baroque period.

According to historian M. Kovalchuk, “from 1888 to 1890, after the enclosing of the Poltva, new, larger, and more varied flower beds were laid in, as well as chestnut, maple, acacia and ash-lined lanes that would provide shady walks through the city’s heart in future.” The territory of the promenade and gardens on the Hetman Ramparts stood at 1.26 hectare (Kowalczuk, 1896, 320). Olena Stepaniv would write later that, “the modern street center goes on for 500 meters through a shady walk, sown in maple, chestnut, linden, acacia, and ash” (Stepaniv, 1992, 47).

Overall, three ‘rings of green’ surround the city of Lviv. The Hetman Ramparts and the promenade along Prospect Svobody, taken together with the Governor’s Ramparts (between Pidvalna and Vynnychenka Streets) and the Galicia, Sobornyi, and Danylo Halytskyi squares, form the first ring and mark the medieval boundaries of the city.

The second ring extends from the eastern bank of the Poltva through Vysoky Zamok, Znessinya, Lychakiv, Pohulyanka, and Zalizna Voda parks; and from the west to Ivan Franko Park and several other, smaller green areas. To the south, this second circle faces the Stryiskyi Park complex.

The third ring is formed by the outlying Vynnykivskyi, Bryukhovytskyi, and Holoskivskyi parklands.

Related buildings and spaces

People

Karl Ludwig. Austrian Archduke.

Michał Kowalczuk (Mychailo Kovalchuk). Architect, architectural critic,

guidebook author.

Adam Mickiewicz. Polish poet.

Arnold Röhring. Landscape architect, park designer.

Stanisław Skarbek. Count, philanthropist.

Olena Stepaniv. Historian, geographer, civic

activist.

Stanisław Jan Jabłonowski. Great Crown Hetman.

Sources

- Ivanochko, U. et al. “Architecture of the late 18th and first half of the 19th Centuries.” Architecture of Lviv: Times and Styles, 13th-21st centuries. Biriulyov, Yuryi, ed. Lviv: Center of Europe Publishing, 2008. 170-237. Print.

- Krypyakevych, Ivan. Historical Walks Around Lviv. Lviv: Kamenyar, 1991. Print.

- Stepaniv, Olena. Contemporary Lviv: A Guidebook. Lviv: Phoenix, 1992. Print.

- Barański, F. Przewodnik po Lwowie: Z planem i widokami Lwowa. Lwów: 1902. Print.

- Jaworski, F. Lwόw stary i wczorajszy (szkice i opowiadania): Z ilustracyami. Wydanie drugie poprawione. Lwów: 1911. Print.

- Kowalczuk, M. “Rozwόj terytoryalny miasta.” Miasto Lwów w okresie samorządu 1870–1895. Lwów: 1896. 299–351. Print.

- Orłowicz, M. Ilustrowany przewodnik po Lwowie: Ze 102 ilustracjami i planem miasta. Wydanie drugie rozszerzone. Lwów – Warszawa: Książnica-Atlas, 1925. Print.

- Stankiewicz, Z. ”Ogrody i plantacje miejskie.” Lwów dawny i dzisiejszy: Praca zbiorowa pod redakcją B. Janusza. Lwów: 1928. 62–71. Print.

Urban Media Archive Materials